More precisely, suicide calls God’s location into question. In reflecting some fifty years ago on his wife’s death from cancer, C.S. Lewis famously wrote, “Meanwhile, where is God? This is one of the more disquieting symptoms [of grief]. When you are happy, so happy that you have no sense of needing Him . . . you will be–or so it feels–welcomed with open arms. But go to Him when your need is desperate, when all other help is vain, and what do you find? A door slammed in your face, and a sound of bolting and double bolting on the inside. After that, silence. You may as well turn away. The longer you wait, the more emphatic the silence will become” (A Grief Observed. New York: Bantam Books, 1961, pp. 4-5).

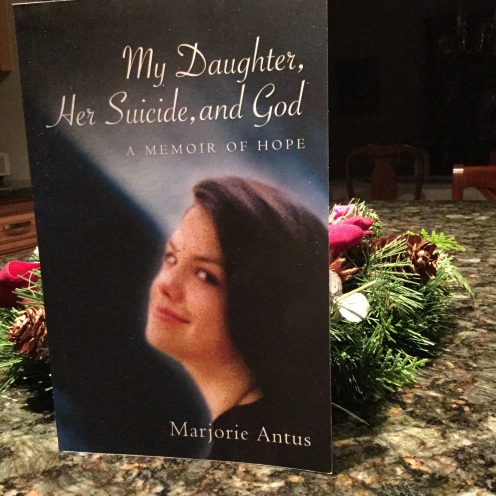

For me, silence was the first indication that something had gone terribly wrong on the day of my daughter Mary’s suicide in 1995. Tapping on her locked bedroom door, I heard only silence as she lay unconscious on her bed. A great deal of noise soon followed as the rescue squad filled the room with equipment and loud, technical language about blood pressure and heart rhythm.

Just after Mary died at the hospital, silence set in again. It was on the short ride home that I noticed it: the presence of profound inner silence which felt like God’s absence.

That moment of disorienting silence was followed by the intense weeping of my family members, thousands of words of consolation at the wake and funeral Mass, agitated and heartfelt phone calls, casseroles left on the front porch that–yes–were speaking, too.

It is true that God seemed to have double bolted the door and left me standing in silence on the other side. It is true that things I “knew” about God’s place in my life were hurled into the air when Mary died. But the human kindness washing over me in early bereavement transformed what would have been horrible days into something decent and fine. There’s no explaining that turn of events except to say God was present in the people who were present to me. And it was obvious.