On the day their son died by self-inflicted gunshot, Iris Bolton and her husband Jack received a visitor who gave them unforgettable advice. That is to say, on a day of emotional chaos with phone and doorbell ringing, neighbors overflowing couches and sitting on the floor, someone offering Iris a stiff drink–on that day, a psychiatrist friend took the Boltons into a quiet room and offered wisdom.

In her classic work called My Son, My Son, Iris writes about Dr. Maholick first describing the grief stages she and Jack were bound to experience–the shock, denial, guilt, anger and depression that “come with the territory” of grief. “And then he added an extra dimension to his counseling that seemed at that moment utterly beyond belief: ‘. . . this crisis can be used to bring your family closer together than ever,’ he said. ‘If you use this opportunity wisely, you can survive and be a stronger unit than before.'”

When Iris asked how such a result could be brought about, the doctor provided a formula. “Make every decision together throughout this crisis. Hear every voice. Work for consensus. Never exclude your children during these next few days. . . . Discuss each problem openly, treating each individual equally regardless of age or experience. . . Grief of itself is a medicine when you are open about it. Only secret grief is harmful. Through mutual helping, you will all heal more rapidly . . .” (My Son, My Son: A Guide to Healing After Death, Loss, or Suicide. Atlanta: Bolton Press, 1996, 16)

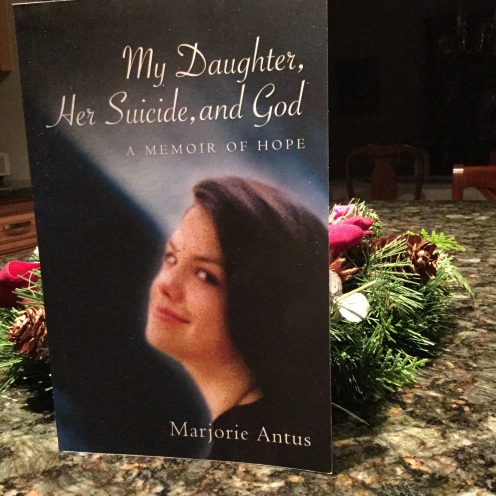

My daughter Mary’s suicide in 1995 left a family of four–my husband John and I along with a 21-year-old son and an 11-year-old daughter. While I subscribe to the doctor’s counsel about a family pulling together after devastation, and while I agree that openness is one remedy for devastation, I think Dr. Maholick understates the effect of shock following suicide. My kids were at a loss for words; John and I were at a loss for words. There were no words after Mary died.

Still, John and I knew we had to put ourselves and our kids in a room with a therapist each week for many months and allow pain and bewilderment to surface. We didn’t ask our kids ahead of time if they thought this togetherness would be helpful. But to their everlasting credit, they went along with it. I’d like to think that, taking the medicine together, we helped each other through the crisis and healed more rapidly. As with most aspects of suicide bereavement, I accept not knowing for sure. But I do know my family survived. We’re in touch; we vacation together as often as we can.