Several days ago, a moving van pulled up across the street and men started unloading the home my neighbors had lived in for fifteen years. I thought maybe the neighbors were renovating and would be moving back in a couple months. “No,” said one son with a grin, “we’re moving, but only a few blocks away.” Even while congratulating Jack, I was saddened by the news. “Why is this move so troubling to me? I’ll still see these folks at Mass on Sundays, and it’s not as though they owed me a good-bye.”

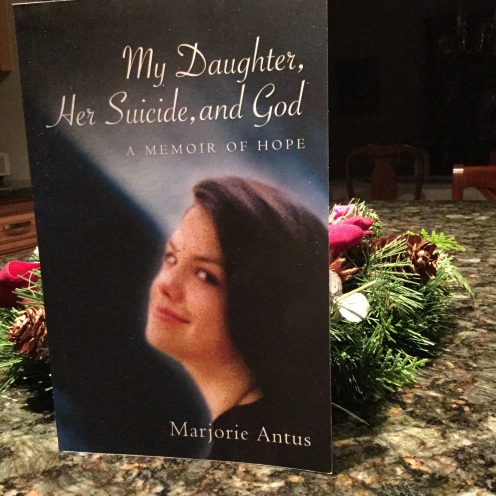

It’s just this: someone did once owe me a good-bye she never gave–my teenage daughter Mary who died by suicide in 1995. Watching neighbors move last week was all it took to renew my sense of abandonment that, while attempting to soothe over the years, I continue to have and hold.

“To the extent that survivors construe the suicide as a willful choice on the part of the deceased,” write clinical scholars John Jordan and John McIntosh, “it may engender profound feelings of . . . abandonment in the mourner. . . ” (Grief After Suicide: Understanding the Consequences and Caring for the Survivors. New York: Routledge, 2011, p. 183).

But I’ve spent years pushing back against the notion of willfulness in Mary’s suicide. I now think she had no choice, given her hopelessness. Just the same, I carry the sting of “no good-bye” right beneath the surface, readily activated.

In Blue Genes: A Memoir of Loss and Survival, Christopher Lukas writes about family suicides and the abandonment he felt and still feels after a relative’s suicide. He describes his experience as an adolescent upon learning that his mother’s death was, in fact, a suicide: “Stunned is what I felt–stunned and startled and hurt. I was furious at Mother. She had taken her own life and abandoned me in the process” (New York: Anchor Books, 2008, p. 138).

About his brother’s suicide in 1997, Lukas writes, “He did not kill himself to hurt me and the others who were his friends. . . But I cannot let go of the fact that by leaving without saying good-bye, he left me, once more, all alone” (p. 244).

I will look for a way to say good-bye to my neighbors just as I’ve looked for a way to say good-bye to Mary. It’s what suicide survivors do. It’s something that can be done.