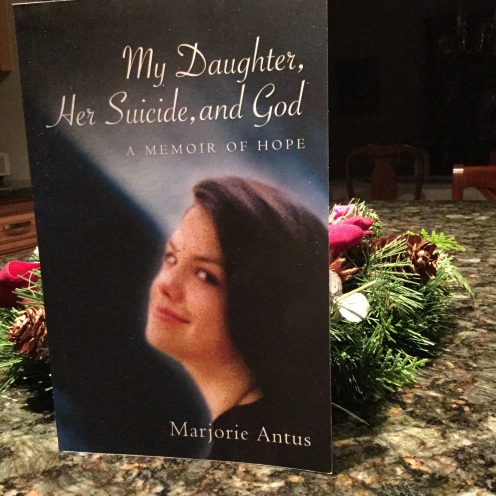

Please meet Mary! Since 2012, I have been blogging about my daughter Mary, and now anyone who wants to know her better can do so. I’ve finally finished writing an account titled My Daughter, Her Suicide, and God: A Memoir of Hope that is now available on Amazon.com.

Please meet Mary! Since 2012, I have been blogging about my daughter Mary, and now anyone who wants to know her better can do so. I’ve finally finished writing an account titled My Daughter, Her Suicide, and God: A Memoir of Hope that is now available on Amazon.com.

Over a period of some ten years beginning in 2001, I took it upon myself to delve into Mary’s death, her life, and the grief of an entire family at her passing. In truth, I was driven to explore some of the “what-if” questions and the “why” torments about which I’ve posted many times. I wanted to find out where God was in the tragedy and ultimately to figure out how to put “daughter,” “suicide,” and “God” together harmoniously in one sentence. But I always knew that the one sentence would arrive, if ever, only after several thousand other sentences.

The writing also became my attempt at mending the shattered relationship that Mary and I shared. I wanted badly to get her back in my life in a good way. Putting words on paper for more than a decade, pushing “delete” and starting over, no matter how laborious-seeming in retrospect (while never actually laborious), did deliver healing in tiny doses and slowly bring Mary back.

A few months ago in this blog, I quoted Fr. Ronald Rolheiser as saying, “Few things stigmatize someone’s life and meaning as does death by suicide” (ronrolheiser.com July 21, 2014).

My daughter’s life held and still holds great meaning, as does the life of anyone who falls victim to suicide. It has been my privilege to bear witness in a memoir to the beauty and meaning of her precious, unrepeatable life.