Late on a rainy night in April, 2002, my mother and I were driving home from a nearby town after watching my brother, George, perform there as “Brandy Bottle Bates” in Guys and Dolls. My extended family had finally begun to enjoy some of life’s pleasures even while mourning the suicide of my daughter Mary that had occurred seven years earlier. So as my mother and I chatted that night, I was also privately searching for answers about Mary as I had done every night: why did she intentionally overdose on her antidepressant medication? How could she do that to herself and to her family? How could she?

Late on a rainy night in April, 2002, my mother and I were driving home from a nearby town after watching my brother, George, perform there as “Brandy Bottle Bates” in Guys and Dolls. My extended family had finally begun to enjoy some of life’s pleasures even while mourning the suicide of my daughter Mary that had occurred seven years earlier. So as my mother and I chatted that night, I was also privately searching for answers about Mary as I had done every night: why did she intentionally overdose on her antidepressant medication? How could she do that to herself and to her family? How could she?

But then this: a white cat running across the road not ten feet from my front wheels. “After a sickening bump under both front and back tires, I stopped on the road, windshield wipers clicking, wondering what to do.

“Drive on,” my mother said. “The cat’s dead, and the owner might live a mile away. I know you feel bad, but there’s nothing you can do.”

I did drive on, but the death of that cat troubled me for days. I visualized the owners finding the crushed body by the road and shouting, “How could you?” at faceless me just as I had shouted at Mary.

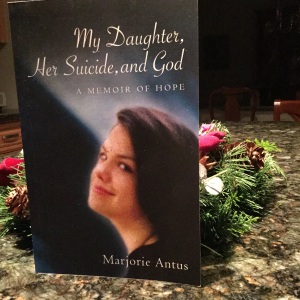

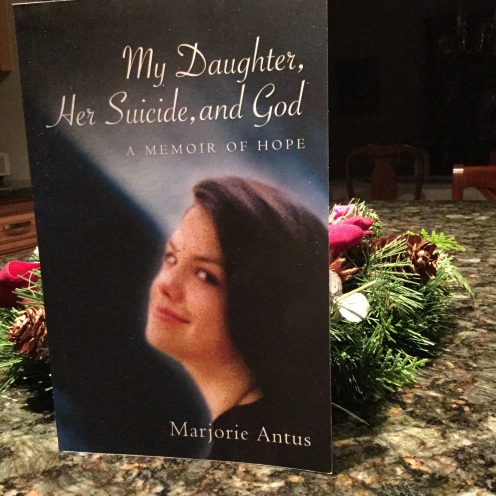

It finally dawned on me that those owners deserved an apology they would never get and that their not getting an apology made me something of a culprit. “I felt for them. I felt for Mary, as well. It wasn’t that I placed suicide and accidental animal slaughter in the same moral category; it was that my daughter and I had both done damage, and neither of us could apologize for it. However, merely imagining that Mary would want to apologize [as I wanted to] put an end to my ‘How could you?’ question and brought peace” (Marjorie Antus, My Daughter, Her Suicide, and God: A Memoir of Hope, CreateSpace, 2014, 198-9).

Then or now, I wouldn’t imagine Mary apologizing for the mental suffering she tried to end (and did end, I believe) with an intentional overdose. The agony of mental illness leading to suicide is described by psychologist Thomas Joiner as a “force of nature” nearly impossible for the rest of us to grasp or expect an apology for (2011 Suicide Prevention Conference: Myths About Suicide, YouTube, Google, Inc.).

Still, it’s restorative to imagine those who have died by suicide apologizing for the heartache, the bewilderment, the life disruption, and the chronic sorrow their deaths have brought. I’m also glad I was able to feel like a wrongdoer for a time. That feeling brought empathy, and empathy brought love.